Data Engineering Project Idea for People Getting into Data Engineering

It can be difficult to make a jump between job titles. I get messages from people who are experienced in analytics and want to transition to data engineering, but they don’t know where to start. I wrote a post on skills you can work on while not data engineering, but I wanted to give an example of a specific project you can do start to finish to showcase your data engineering skills.

If you want to break into data engineering, you can try similar projects. You can describe your project on your resume and in interviews, giving you something to talk about in place of data engineering professional experience. Consider posting your code to Github or Gitlab and linking it on your resume and LinkedIn.

The general structure of a good data engineering practice project is:

- Extract a data set from a system or source

- Store that data in a database

- Display the accessibility and usability of the data

Regarding the last bullet point, data engineers don’t do much data analysis, but I think it’s important when we do a project like this not to just say “the data is in the database, trust me, it’s there. I didn’t show it to you, but it’s there. Glad we agree.” We want to show how people could use this data to make business decisions, and we want to do some basic quality assurance.

Step 1: Extract a dataset

For this project, I knew I wanted a dataset having to do with cats. I searched on Google Dataset Search for anything usable. When looking for a dataset, I generally want it to be big enough to extract some trends (so not 10 rows of cats), and to contain both attributes and measures. What I mean by this is that we want fields that describe a cat, but also some metrics we can aggregate to show trends about cats over time.

I found that Sonoma County has a record of their adopted animals since 2014. This shows the intake and outcome data for all cats that come through the shelter. I immediately started thinking of some questions this dataset could answer: how long does it take a cat to get adopted? What breeds are adopted fastest? When are cats most surrendered? Being able to think of several questions a dataset can answer is a good sign that it is worth building a project out of.

Ideally, we want to hit a live source for our dataset, meaning we want to be able to hit the source and retrieve updated data each time. Using a stale dataset, such as a manually downloaded CSV, is a good first step, but we want to demonstrate scalability in our project. I recommend either trying to hit an API or using the requests module to hit a URL. I was lucky that Sonoma County had an API endpoint.

hot tip If you find an API you want to hit, see if it has any documentation. They often do and this will save you some time. In this case, there was documentation with sample code. I used some of the sample code under Python, although I did not use pandas.

This code points to sodapy, which I had to PIP install.

Step 2: Store that data in a database

2a: Hit the API

We will be using sqlite3 to interface with sqlite. sqlite is not a RDBMS that you will use professionally, but, when practicing Python, it’s the fastest option to set up and use.

import sqlite3

from sodapy import Socrata

// this code and comment were taken from the documentation above

client = Socrata("data.sonomacounty.ca.gov", None)

results = client.get("924a-vesw", limit=25000)

Whenever possible, we should use the data available in the source to QA. In this case, I can tell that there are over 20k rows, so we want to make sure our limit encompasses everything. When this goes to production, the limit should be removed.

Once we connect to the API, we want to filter for cats and store the data:

cats = []

for pet in results:

if pet["type"] == "CAT":

cats.append(pet)

2b: Write to the database

We need a connection to SQLite. Generally, I make connections to databases classes in Python. I stole this one from here. SQLite databases are really files, so we have to define where to store that database.

CAT_DATABASE = "/Users/alisaaylward/Desktop/sqlite/cat.db"

def create_connection(db_file):

# create SQLite database, from https://www.sqlitetutorial.net/sqlite-python/creating-database/

""" Create a database connection to a SQLite database """

conn = None

try:

conn = sqlite3.connect(db_file)

except Exception as e:

print(e)

finally:

if conn:

conn.close()

# lets pretend sqilte can't handle JSON

# create db

create_connection(CAT_DATABASE)

# connect

dbconn = sqlite3.connect(CAT_DATABASE)

cur = dbconn.cursor()

I usually prefer not to INSERT directly into databases tables; writing semi-structured output from an API, such as JSON, into a datalake is a safer option. If you store JSON the code will be more scalable and flexible: a change in a field name or a removed field will not break your code. For ease, we will write directly to our SQLite databases, but when you work on enterprise solutions with databases other than SQLite and datalakes, I encourage you to think about how to make sure your code can live through upstream changes.

hot tip Upstream data will change.

Because I have the documentation, I know the fields names and the fields I want to use.

I will also be doing a truncate (a delete in SQLite) each time. This is also not best practice since you will lose all history. Even if you don’t have a datalake, consider creating a history table with continuous inserts and metadata timestamp to deduplicate.

Notes on documentation

Whenever you get data from a data source, try to see if the source can tell you some basic facts for QA. In this case, the metadata indicates there are 20.5K rows and 24 columns. This will help you be confident, once you bring in the data, that you got all the data and only the data. It then goes on to define each of the columns. This is valuable stuff; I assure you, any data you bring in, people will want definitions. They are needy people, analysts. Always wanting definitions.

Often when we think about definitions, we think about just defining the field. But if the fields have a finite amount of values (sometimes called an enumeration, enum, or picklist), those may need to be defined too. For instance, a color field may have the options of values red, blue, and green. These likely do not need definitions for a general audience. However, the values can be jargon or codes that need definitions. In this case, some of the field enumerations are defined here. It is not intuitive that “TREAT MAN” means “Treatable/Manageable: The animal has a chronic health or behavior condition that can be treated or managed.” That would not have been my guess.

In addition to helping end users, all this documentation allows me QA better. Since I know what the fields mean, I’ll be able to apply intuition to the numbers I chart and notice any anomalies. Definitions aren’t just something you paste into the data dictionary at the end of your project; if used properly, they can help you build a reliable data pipeline.

Back to the code:

CAT_DATABASE = "/Users/alisaaylward/Desktop/sqlite/cat.db"

FIELDS = ["id", "name", "color", "intake_date", "sex",

"days_in_shelter", "size", "intake_subtype", "breed", "intake_condition",

"date_of_birth", "intake_jurisdiction", "intake_type", "outcome_date", "outcome_subtype",

"outcome_condition", "outcome_jurisdiction", "outcome_type"]

CAT_TABLE = """

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS cats_all

(

id TEXT,

name TEXT,

color TEXT,

intake_date DATE,

sex TEXT,

days_in_shelter INT,

size TEXT,

intake_subtype TEXT,

breed TEXT,

intake_condition TEXT,

date_of_birth DATE,

intake_jurisdiction TEXT,

intake_type TEXT,

outcome_date DATE,

outcome_subtype TEXT,

outcome_condition TEXT,

outcome_jurisdiction TEXT,

outcome_type TEXT,

updated_datetime DATETIME

);

"""

INSERT_STATEMENT = "INSERT INTO cats_all VALUES"

Now that we have our connection and our SQL, time to put it together with an insert! In SQLite you can do multi-value inserts, as opposed to Vertica. In Vertica, you have to do multiple INSERT statements or use a UNION. However, SQLite has a limit of 500 values to insert (Source). Snowflake limit is 16384, so it varies by database, so always check on your database limits before an insert (Source). As a result of this limit, we want to loop over every row and insert at the 500th row.

### create table

cur.execute(CAT_TABLE)

INSERT_COUNTS = 500

value_list = []

## loop over every 500

total_cats = len(cats)

times_around = int(math.ceil(total_cats / INSERT_COUNTS)) + 1

for loop_around in range(0, times_around):

for cat in cats[loop_around*INSERT_COUNTS:(loop_around*INSERT_COUNTS)+INSERT_COUNTS]:

this_list = []

# parse the JSON

for field in FIELDS:

## avoid TypeError: sequence item 1: expected string or Unicode, NoneType found

if cat.get(field) is None:

cat_field = "NULL"

else:

cat_field = cat.get(field).replace("'", "")

this_list.append(cat_field)

value_list.append("', '".join(this_list) + "', strftime('%Y-%m-%d %H-%M-%S','now')),")

insert = "(\'" + "('".join(value_list)

## ensure it's empty

cur.execute("DELETE FROM cats_all")

## insert

cur.execute(INSERT_STATEMENT + insert[:-1] + ';')

cur.close()

And now, we have wonderful data!

cur.execute("""SELECT * FROM cats_all""")

rows = cur.fetchall()

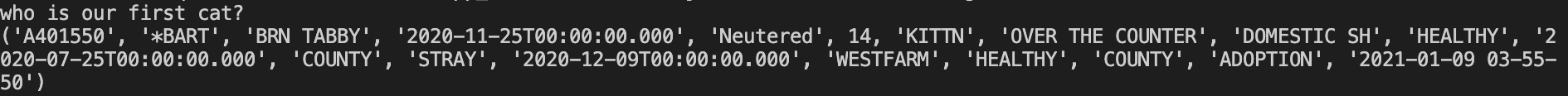

print("who is our first cat?")

print(rows[0])

Step 3: Display the accessibility and usability of the data

Extracting meaningful analytics from data isn’t my day job, but it is my job when I bring in a new data set.

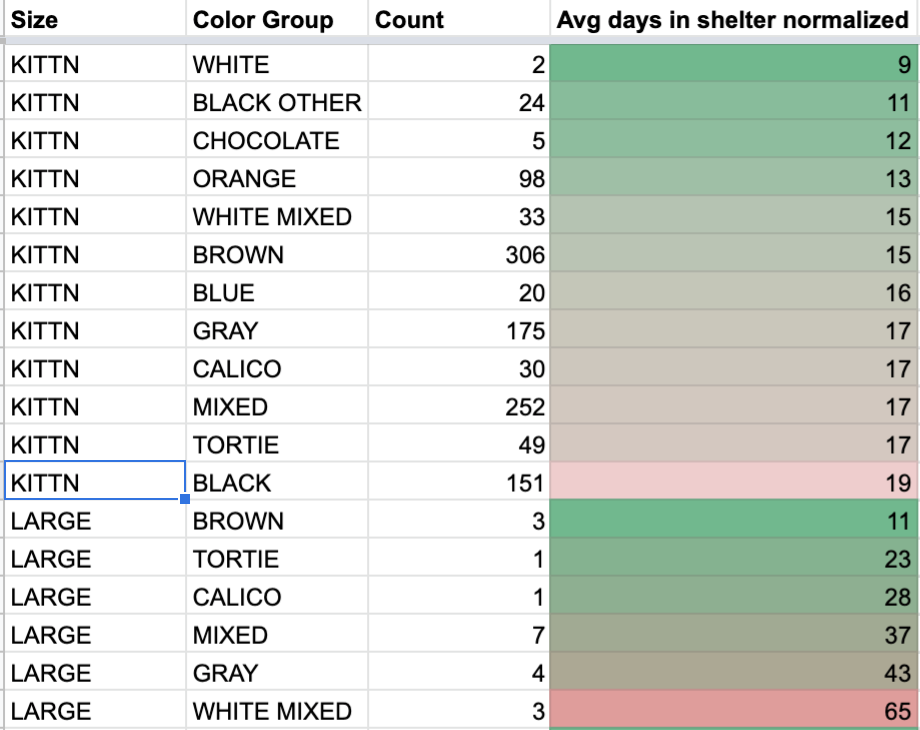

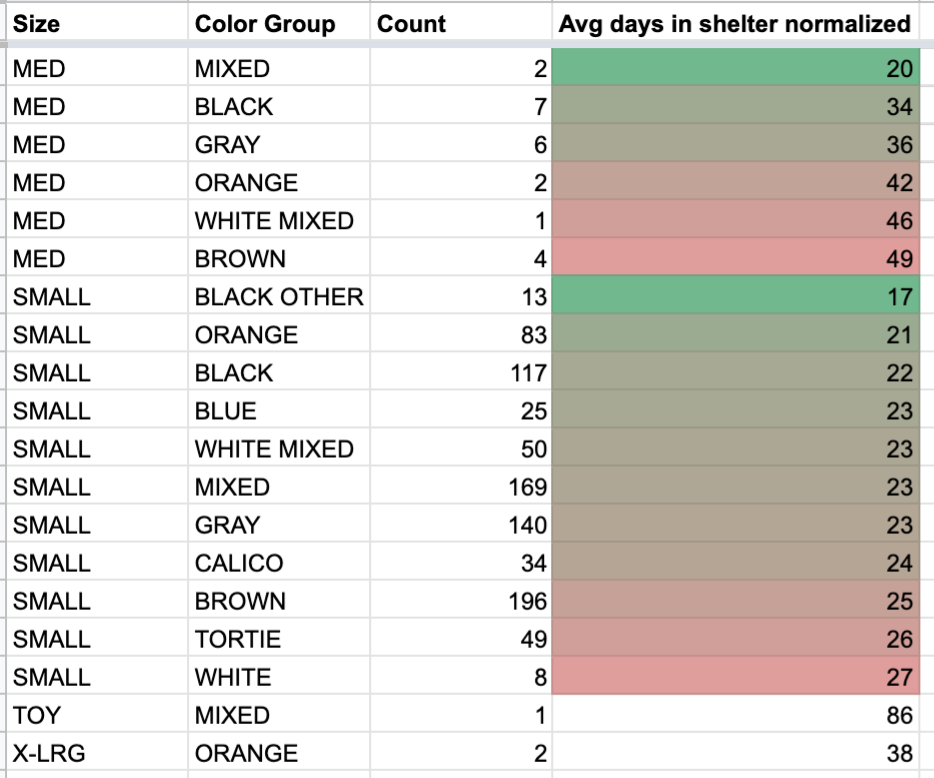

The business question I tried to solve was: does color impact how many days it takes a cat to get adopted?

After playing with the data, I found that the small set size and inconsistent color and breed information made it hard to extract some trends. BLK TABBY/TORTIE is a color, as is BLK TABBY– you tell me how to group that together. I had to combine color values with my intuition.

I also had to “normalize” the data; a cat can’t be adopted until it’s spayed or neutered. Although the age at which cats are spayed and neutered varies, the youngest adopted cat during this time period was 48 days. Therefore, days at the shelter should not count towards the average days to adoption until they’re associated with a kitten older than 48 days. We also want to filter for cats with intake type HEALTHY, since any other intake type may be delayed by behavioral or medical treatment.

I also had to group by the size field since, well, kittens go faster than older cats so it skews the results if there are a lot of kittens of a certain color.

Our analytical query is:

cats = cur.execute("""

SELECT size,

CASE WHEN upper(color) = 'BLACK/BLK TABBY' THEN 'BLACK'

WHEN upper(color) like 'BLK%' THEN 'BLACK OTHER'

WHEN upper(color) like 'BLUE%' THEN 'BLUE'

WHEN upper(color) like 'BRN %' THEN 'BROWN'

WHEN upper(color) like 'BROWN' THEN 'BROWN'

WHEN upper(color) like 'BUFF%' THEN 'ORANGE'

WHEN upper(color) like 'ORG %' THEN 'ORANGE'

WHEN upper(color) like 'ORANGE%' THEN 'ORANGE'

WHEN upper(color) like 'WHITE' THEN 'WHITE'

WHEN upper(color) like 'BLACK' THEN 'BLACK'

WHEN upper(color) like 'TORTIE%' THEN 'TORTIE'

WHEN upper(color) like 'WHITE/%' THEN 'WHITE MIXED'

WHEN upper(color) like 'GRAY%' THEN 'GRAY'

WHEN upper(color) like 'CALICO%' THEN 'CALICO'

WHEN upper(color) like 'CHOC%' THEN 'CHOCOLATE'

ELSE 'MIXED' end as color_group,

count(*),

avg(case when days_at_intake < 48

then days_in_shelter - (48- days_at_intake)

else days_in_shelter

end) as days_in_shelter_normalized

from (

SELECT *,

julianday(intake_date) - julianday(date_of_birth) as days_at_intake,

julianday(outcome_date) - julianday(intake_date) as days_in_shelter,

julianday(outcome_date) - julianday(date_of_birth) as days_at_adoption

FROM cats_all

where outcome_type = 'ADOPTION'

and intake_condition = 'HEALTHY'

)

group by 1,2

""")

for cat in cats.fetchall():

print(cat)

Even with the conditional formatting from Google sheets, there isn’t a lot to conclude, The only thing we could maybe say is that, on average, black, healthy kittens spend a few more days in the shelter before getting adopted.

This is absolutely ridiculous based on anecdotal evidence given that we adopted Mac and Cheese the day after they got spayed and neutered.